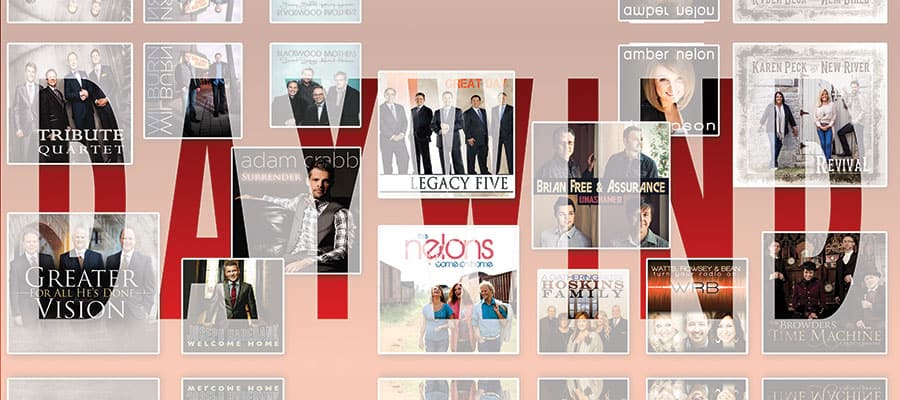

INDUSTRY UPDATE: Ed Leonard, President of Daywind Records, Celebrates 21 Years

Ed Leonard was born for this. As the son of Daywind founder Dottie Leonard Miller, Ed has witnessed first-hand the company’s growth from a start-up in a garage to a multi-faceted cornerstone in the Christian music industry over the last 27 years.

Ed recently has served 21 years at Daywind Records, including the last 10 as President, and he’s helped position the company to move beyond its strong Southern Gospel reach. Despite the instability of the music business, Daywind is positioned for further growth well into the future. Here’s a look at how Daywind has remained “open” through the changes, rolled with the shift to streaming and explored new publishing territory for greater success.

The industry is ever-changing. What are some of the biggest changes for Daywind in recent days?

We hired Chad Green, who used to be at Word and was at ASCAP for many years before that, to direct our publishing efforts on the AC side of things. We signed writers Sam Tinnesz, Aaron Rice, Michael Fordinal, Justin Kintzel, and Hearts of Saints. We have cuts on the new Mandisa record, we got two cuts on the Natalie Grant record, a cut on Hawk Nelson’s record, a Newsboys cut, and Jeremy Rosado. We’ve never had that before. Sam Tinnesz has been the leader of the charge. He’s been such a great writer to build a company around. Add Aaron and Michael to that and you have an incredible core.

Can you tell us about the decision to broaden your publishing base?

The “strategy” is really just openness to opportunity. My mom started this company. Her name is Dottie Leonard Miller, and she started the company out of a garage 33 years ago. She had a passion for working with Christian retailers. She was working at a small label, with a $10,000 investment from her father, her brother and her friend. She basically set up a computer in our garage and started calling up stores. She would order product in from independents, then majors, and it just became a real service-oriented music distribution company called New Day Christian Distributors. She realized quickly that the margins were awfully tight when you have to distribute somebody’s product that’s already being distributed. You’re another middle man , so your margins get really tight. In order to survive, she had to develop some product of her own so that the margins were better. She started doing performance tracks with her friend Ronnie Drake and then that opened us up to, okay, you do soundtracks, you start getting in the studio, you start getting involved with people—producers, musicians, all that kind of stuff—and then the record label is a natural. You’re good at Southern Gospel and distributing to independent, you’re already in the studio recording products, and then you run into an artist who has all those needs and you’re like, ‘Let us be your label. We’ll do your distribution, we’ll do your project, we’ll help find you songs, we’ll help you get opportunities and grow as an artist.’ And then the record label starts. She has always been open to trying things. Her openness to whatever—doing a record for someone who’s never done a record before, running a contest, trying to get into the CCM and choral market—that all starts with an investment, somebody who’s willing to write a check and say, “I’m trusting in God that this money will be well spent in trying to reach people with its message, you know? It’s a lot of spiritual openness from her that drives everything.

How difficult is it to remain open when the industry shifts and you encounter a season when things aren’t as profitable?

Yeah, I think there’s a natural retraction that happens, at least initially, when you see things are starting to not go as well. You have to force yourself to look for other opportunities. Just on the New Day side—I’m sorry I’m jumping around the different companies, but we really do have so much here, it’s hard to narrow it down to just making records. But let’s say probably six or seven years ago when music really started to slow down, she recognized fairly quickly that if the distribution company was going to keep its doors open she was going to have to diversify her product base, because it was 99% music or music-related products: DVDs, CDs, sheet music, whatever it was. So she sent one of our employees Michael Turner to Toy Fair and said, “The toy market in Christian retail is fairly underserved. Everybody has book and church supplies covered, and music. What else could sell in Christian stores and be a witness tool that we could be a part of getting into that market?” We worked out deals immediately with people like Fisher-Price and ended up working with a company called Melissa and Doug, which is a really major independent toy company. These people were already in the Christian market directly, a little bit, but they had not gone beyond maybe a couple of the chain stores, so we were able to take their products and get them some wider recognition and all that stuff. Again, it all leads to the one effort that leads you down a path. You asked me early on what are some keys to the success, and I think one was the spiritual openness, but the second thing is having a champion for whatever you do. You can sit there in a room with five people and say, ‘We’re going to go start a publishing company,’ but if you don’t have champions for that, somebody who lives, eats, breathes, sleeps it every day, and is really excited and passionate about building something like that, no matter how much money you throw at it, it’s not going to work. You have to have that champion, someone who is willing to put their resources and that effort into it. And sustain it. Not necessarily throw money at it, but you have to sustain the effort. You can’t start and stop; if you don’t have the champion, you’ve got to go find the champion or develop a champion from within, maybe someone you’ve got working in another area. You point them in that direction and they just take to it. They go and turn over rocks and try to find opportunities out there.

What’s the biggest hurdle in front of Daywind right now?

Trying to transition from—on the record side now—being a product company to being a service company. That’s what I see us developing into. We are going to get involved in events and consulting and other mediums like social media, which we’re involved in now, but obviously it’s more involved in the internet and television. It’s figuring out ways to expose the music and then monetize what we expose. The music business is just hard. I can’t think of a word that’s a better match than “hard.” When you have to fight with free or cheap, you’ve got to have some compelling argument. The great potential of digital music—iTunes, Spotify—is right at our fingertips and ears, but the ability to sustain investment in those things is… it used to be, you’d put money into a record and you knew, no matter what, that you were probably going to sell 10,000 records. That’s not a tough business model to work. I mean you could feel confident that you’re going to sell the 10,000, you can feel that that yields, $80,000 in revenues or something like that when you sell it wholesale per record, and then you do so many records and you’ve got a decent stream coming in. But when the $15 CD went in the digital state to $10 for that CD, for that grouping of songs, and then the segregation takes it down to you can buy that single for $1.29, then people would just try to buy the single. Well, you just cut your whole business to a tenth of what it was, and then when you throw in what Spotify does and the like, and Pandora, the ability to literally to listen to the song like a jukebox whenever you want, wherever you want, for free to a small fee, and you’re getting paid per listen like $0.0004. I mean just do the math. It’s really, really hard. So labels have to reinvent themselves and they have to be open to partnerships and they have to be open to sharing with their artists more than they ever have.

Are there more doors open for artists than before?

I think they are. I think if you’ve got talent, and you’ve got some level of support on your own as an artist and make a splash, I think it’s easier to get a record deal today than ever, probably. I think though that you probably, because of the economics, have to be willing to give up more to get the best. Remember, at the end of the day, we’re talking about investment of time and money, so it’s almost like a venture capital thing. You bring your widget, which in this case is creativity and potential, it’s not just the one product, it’s the brand. It’s almost like you’re an inventor—whatever the potential inventions are going to be is the key. That’s kind of the best way to put it with regard to music, but in order to get a return on that investment, you’ve got to be willing to maybe give up more than you gave up before, maybe different revenue streams, or at least sharing the environment. And then the artist would say, ‘Well I can just do this myself. I can build a fan base, I can get myself on television, I can get myself in print, I can get myself on radio, I can get myself into the stores.’ And all of that is true. They can make their own t-shirts, book their own dates, but there’s still a need for somebody who’s going to invest in you and help you do that. Because yes, it’s true, you may do that, and if you’re one in a million, you might make that work on your own. But 999,999 are not going to make it without help. ? So for those people, the label model is still viable. Where you’re working with people who are helping you hone your craft, or you’re working with people who have connections, who know people who will take their call when they won’t take yours, or they won’t take yours for five years. That’s where the label model is still viable, if the artist’s mentality shifts to recognize that many of them still need it. But for those who don’t need say a major label, , the beautiful part is they have more access to more people or companies or whatever who specialize in the different areas that they might need than ever before, because you’ve got all these people who have been trained by major labels, who are out there either operating independently or working for smaller companies or whatever. So there’s never been a better time in history to be an independent artist with all of these resources at your disposal, I would say.

.png?width=352&name=FOR%20SQUARES%20(92).png)